Fourth grade was the year things started to change. In third grade, all the girls in my class were still too scared to watch Are You Afraid of the Dark, and you still got bragging rights for bringing a coloring book to school that had peel-off stickers in it. In third grade, you still had to invite everyone in your class to your birthday party, because friendship was not about personality similarity, it was about who lived closest to your mom's house. Third grade was blissful and simple. Fourth grade was a battlefield.

This is because when children turn nine, they go from assuming the best in everyone to assuming the worst. The Center for Child Development says this is because nine is the age when children begin to enter the "middle childhood" stage, and develop a deeper sense of independence. I am more inclined to believe that if satanic forces do exist, they are especially susceptible to children who are nine.

In fourth grade, my friends started to turn on me. They stopped thinking my impressions of Jackie Gleason were hilarious and began finding sparkle lipgloss super interesting. They started wearing jeans (where we had all previously been just fine in polka dot leggings and T-shirts with kittens on them); they started listening to Z100 Top of the Charts Radio; they started hanging out with each other on Saturdays to "go to the mall or whatever." I am saying "they" because I missed the memo. I didn't know we were supposed to change. It was like watching Noah's Arc disappear into the horizon: I had been left behind.

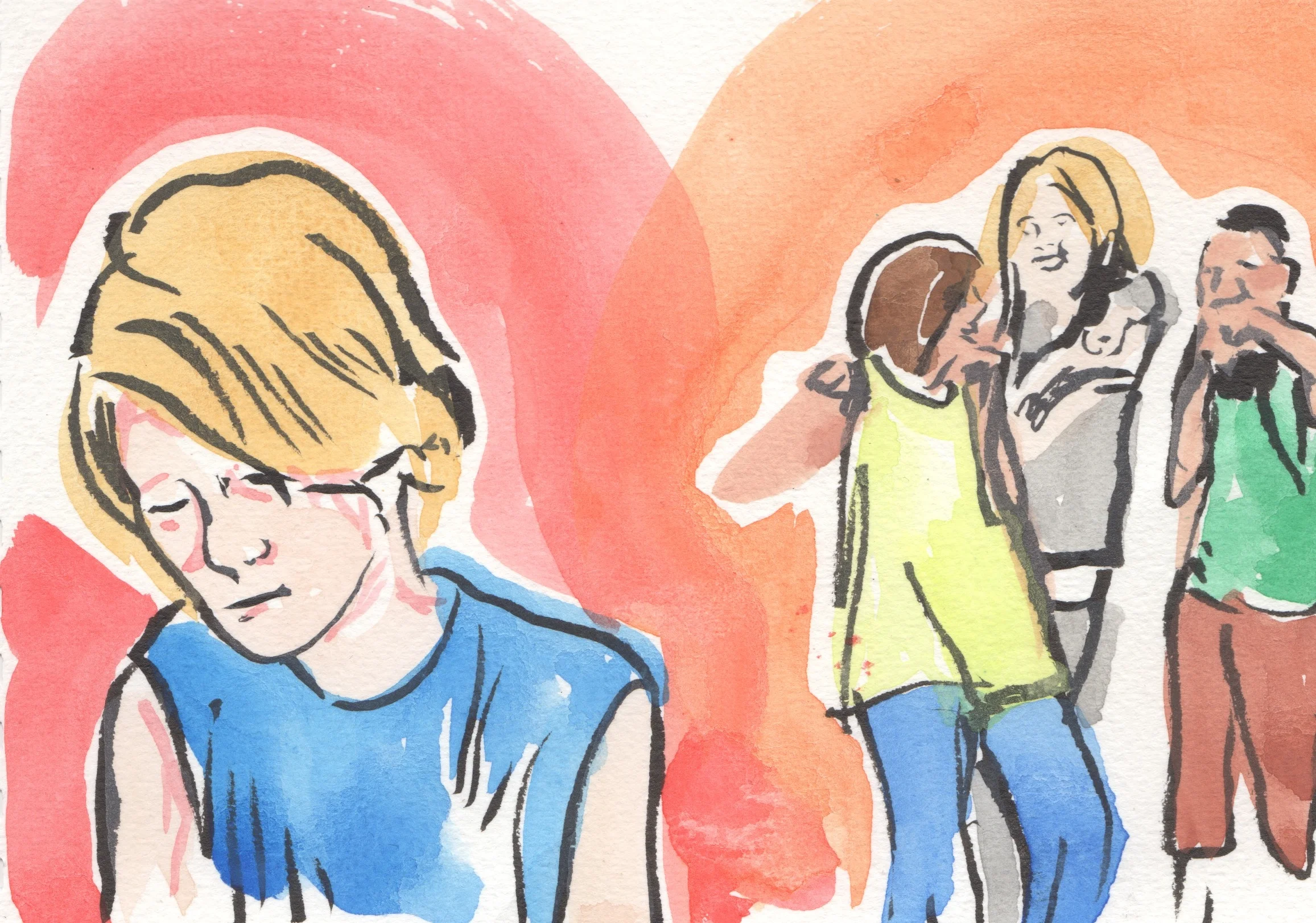

I went to school in my third grade leggings-and-T-shirt combos and continued to read American Girl Magazine at recess. My friends started peeling off, one by one. They stopped inviting me to play "Let's Pretend We're All Talking Horses" (or whatever they were playing at recess). Pretty soon, the favorite recess game became "Whenever Sophie Approaches Us, Run As Fast And Far As You Can, And Then Collapse In Laughter." (I don't know if this was the actual title of the game, because I never got close enough to anyone at recess to ask them.)

Then came the birthday parties. I knew all the birthdays of the girls in my class, because I have an outstanding memory, and I recorded them in my diary. Birthday after birthday would pass; I brought homemade cards to school, because Kelsey Capper told me that none of the girls were going to have parties that year, since birthday parties weren't cool anymore. I believed that, because so far, fourth grade girls defied all translatable logic. Sarah Betts was the one who let it slip during safety patrol duty that all the girls had been having parties behind my back. Her birthday was that weekend. Surely I understood that she couldn't invite me -- how would it make her look? I cried so hard to my mom that eventually my mom must have called Sarah's mom and Sarah was forced to invite me.

During the party, the other girls made a tight-knit circle on the back lawn and painted each other's nails. I helped Sarah's mom wrap hot dogs in biscuits. She thought my Jackie Gleason impression was hilarious.

Don't get me wrong here: I wasn't really a victim so much as I was completely clueless. I failed to change at the same rate as the other girls. Honestly, I failed to change ever. I still act basically the same way I did when I was nine. I was habitually passive-aggressively bullied through eighth grade, and after that I found friends from other schools who were also hopelessly uncool and had remained relatively unchanged throughout their childhood. In high school, it all starts to matter less, anyway. The gregarious confidence that is adorable in a seven-year-old is nice social capital for a high schooler. It's societal suicide in middle school.

--

I'm spending the summer teaching fourth grade LEAP test remediation at a public school in New Orleans. That means I am working with the kids who didn't pass the state standardized test the first time around, and are getting a second chance now. I don't mean to generalize here, but they are all nine-year-olds. They're not all necessarily nine years old in scientific terms, but they all act like the nine-year-olds I went to fourth grade with. They're self-conscious and mean to each other and really into TLC. (Some things never change.)

My first day, I was chewed up and spat out. I tried to teach the boring LEAP material in a fun and quirky way. The nine-year-olds did the student-teacher equivalent of not inviting me to their birthday party: they talked through the lesson and sucked their teeth at me. I threatened to give one girl a consequence. She laughed, "You're too weird and fat to give me a consequence." I did cry, but I'm proud to say, not until I got to the back of the room where no one could see me. The other students made paper planes out of packet pages.

This was the moment that I realized that the nine-year-olds in the LEAP test remediation classroom weren't the only ones acting like nine-year-olds. I was being the biggest nine-year-old of all -- acting just the way I did when I was actually nine; hiding and crying and willing time to accelerate. But this time it wasn't cute. This time it was unacceptable.

The thing is, nine-year-olds need grown ups. Nine-year-olds need Sarah Bett's uncool mom to intervene every now and then to make them feel protected. This is very confusing to me, because I have spent the last seven years trying to understand what is so great about being a grown-up. Frankly, children seem to have way more figured out than most grown-ups I know. I don't think it's appropriate for grown-ups to put rules in place that don't make sense; I don't even really think it makes sense for grown-ups to enforce most rules that do make sense. I am a strong believer in letting kids figure things out for themselves.

However. Children who are bullied deserve to know that life gets better. They should be allowed to feel like if they're in the presence of an adult, they're safe. I want kids to feel safe around me, even if I am uncool, and even if I do still wear polka dot leggings with T-shirts on top.

On my second day teaching summer school, I lay down the law. I told the kids that I didn't like the test or the work packet either. I told them that it felt unfair to me, too -- kids sitting in a classroom during the only time in the year when their time was truly theirs. I promised them recess. But -- and this was key -- there weren't going to be mean words in this room. People who said mean words were going to have to leave.

I sent six kids out on that day.

Sending six kids out felt horrible. I hated feeling like I was parading my power around; forcing "respect." But the other kids seemed grateful.

And the next day, I didn't send anyone out. There weren't mean words. And that was the best I could do.

Sometimes the best you can do is not good enough. It's hard to go into work every day to pedal an agenda I don't agree with, and put up with a consequence system that seems penal and forced. This isn't enough. This isn't what children deserve.

It is, however, what I can do right now. I can be a grown up, even if I don't feel like one. I'm scared of this system, but I can act brave in the face of it. At least one person in the classroom has to be brave in the face of it. That person ought to be the teacher.