At school this year I am taking a class called “Scientific Illustration.” It is a class held on the ground level of Chicago’s Field Museum, taught by Peggy MacNamara (whom I have decided is my spirit animal, but more on that later). It consists, weekly, of spending six hours sitting in front of something — just one thing — and attempting to draw it.

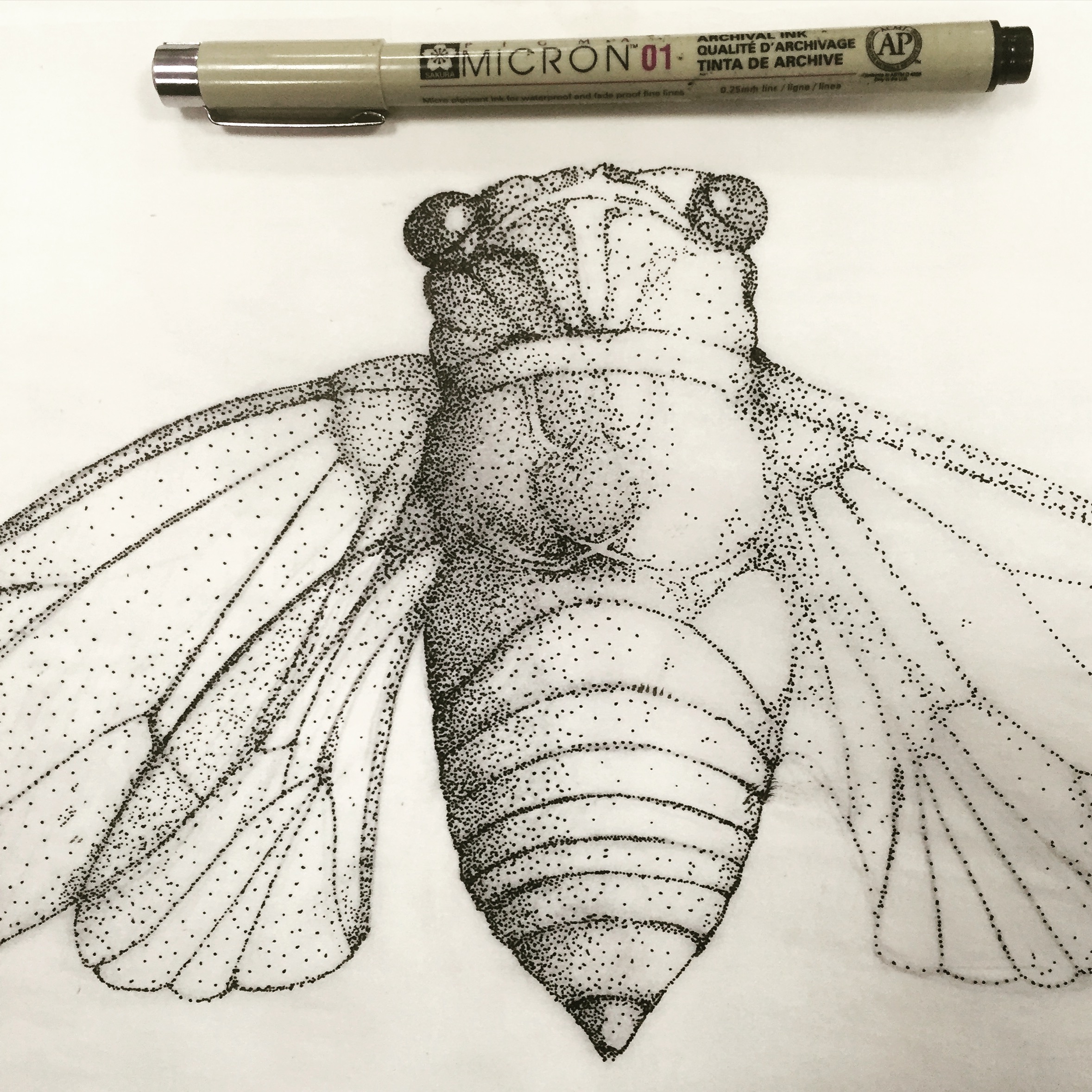

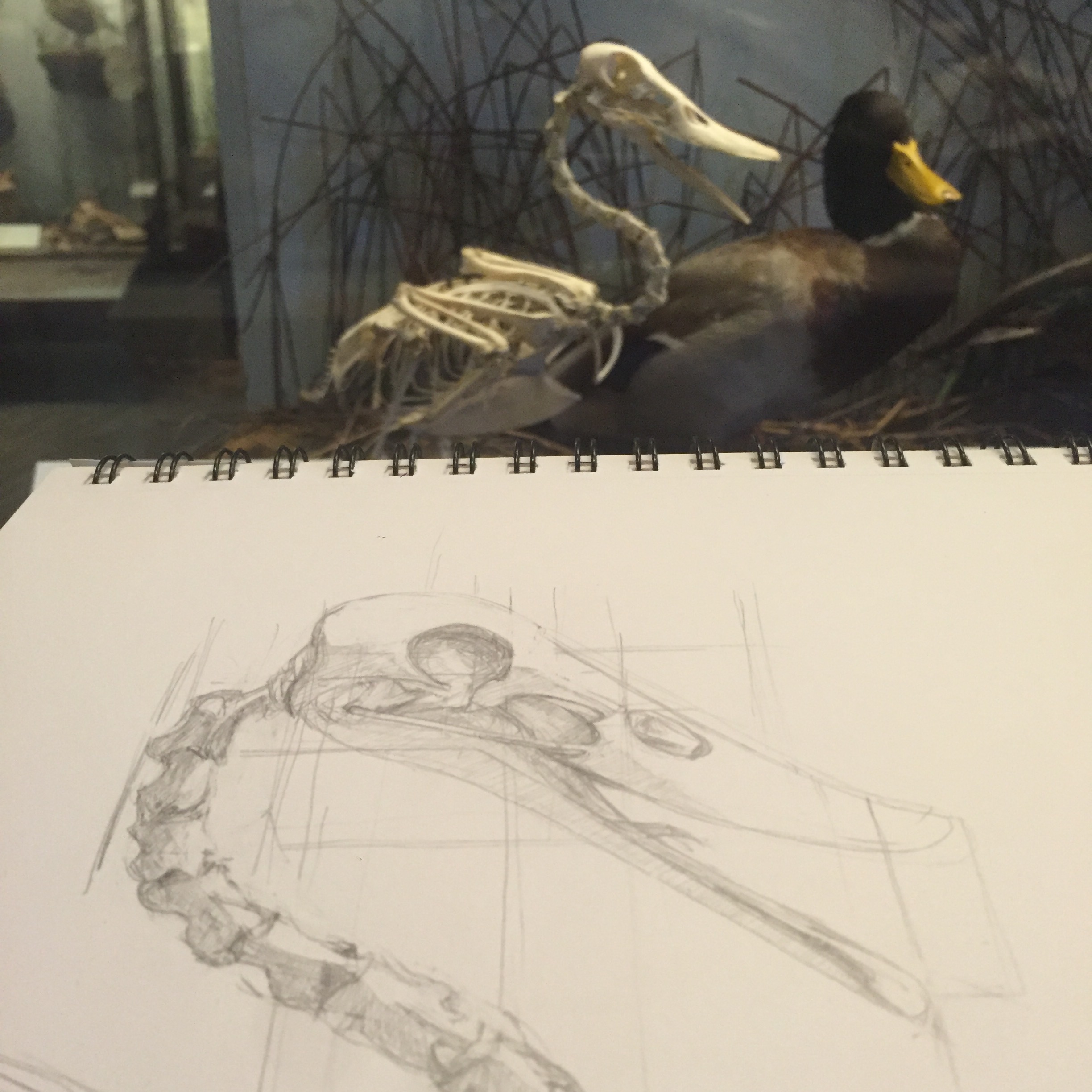

Seriously: Just one thing. I’ve been in the class for six weeks now, and I have six drawings: a hawk, a kakapo, an owl, the skeleton of a duck, a cicada, and a bronze statue of a human man surfing. There are two things you should know about me before we move on: (1) I am the kind of person who works fast. I like to work fast because if you slow down you realize what you might be doing wrong and you give up. Best to move through things; make your mistakes and learn from them and start again. Write fast, draw fast, read fast, and squeeze as much out of life as it can bear. And (2) I have never considered myself to be a person who can draw.

If you know me at all, you are rolling your eyes. You’re saying: Sophie, you draw all the time. Drawings are all over this blog. Don’t go fishing for compliments by saying you can’t draw. Well, reader, it is fine that you think that. I like drawing and I can tell that with practice, I have improved at drawing. But Peggy Ma

cNamara’s class has taught me many things, and among them is that my hunch that I could not, until six weeks ago, draw was absolutely correct.

If she were reading this, Lynda Barry might shake her head at this last sentence. Lynda Barry (whom I love so much that her portrait is literally tattooed on my arm) wants everyone to draw. She wants everyone to unlearn the idea that drawings could be right or wrong; to let go into doodles and scribbles and creative energies that have been silenced because they were told they weren’t serious enough. I love this philosophy, and insofar as Lynda Barry means the word “draw,” I have always been able to draw. And so have you. And so have we all.

But I am lately interested in the idea that two thoughts that seem mutually exclusive — that are so opposite they appear irreconcilable — can, in fact, both be true at once. It is uncomfortable to accept that there is no one right way, which is why we are taught that you can’t be both angry with someone and happy for them; or depressed and euphoric; or love pigeons the most out of every bird and sparrows the most out of every bird. But I think that the human capacity for complexity is deeper than we are taught. I want to hold competing truths all at once. And so: I am a person who can draw, and a person who cannot. Peggy’s and Lynda’s philosophies about art can live together as fundamentally true at the same time.

To prove this to you, I’d like to invoke the bird room. The Field Museum has this incredible room where there is every possible bird you can imagine, meticulously taxidermied (not a verb, but it should be), and displayed in logical groups. There is, for instance, a whole wall of gulls. I am a bird person, and so I am magnetized by the bird room. Of course I would prefer to be with living birds chatting and hiding in the wild; but I would also prefer a fantasy world where I can be in a room with birds from a hundred different biomes all at the same time. See? Both at once.

That, however, is not what I’m trying to prove to you here. Stay with me. I have spent most of Scientific Illustration class in the bird room, drawing birds. I sit on a maroon folding chair and measure with my pencil out in front of my face and my eye closed how far the beak is from the eye is from the feet. I draw squares and do what Peggy calls “crawling:” moving my pencil along the page without lifting my hand, noticing every crook and crevice on the bird’s body. And then I erase. I erase and redraw and erase and eventually, I figure out how to make the bird look right.

One day, while I was drawing the duck skeleton, Peggy came up to me and said, “Oh good. You’re measuring. Some of the students aren’t measuring, and it’s driving me nuts.” I got up and she sat in my chair so she could see if I was seeing correctly. With one eye closed, measuring the beak, she said, “Daniel asked me earlier, ‘Why does it have to be right?’ And I think that’s a very good question.” She paused.

“You should try to make it right because God made it this way. And I’m not telling you to believe in God, or that God is real; I’m saying … this has worked for the duck for millions of years. There is a reason for this design. This art,” and she indicated to the bones, “I’m sorry to say, is better than anything that can come out of the mind of a 20-year-old kid.”

And that is true.

I’m not telling you to believe in God, but when you spend six consecutive hours with a bird skeleton, you might begin to see how totally strange and amazing it really is. You may think you know — I used to think I knew — but I didn’t; not until I sat with it for all those hours and stared at it, and crawled all around it with my brain.

She said it again in a different way yesterday. This was when we were in the room upstairs where women sit on stools and pull organs out of birds that have flown into windows so they can stuff them with cotton for research. That room was also full of bones. Peggy picked up a rib cage and twirled it around on her finger.

“You see, this is the kind of thing that makes me want to really look. This is what makes me want to notice. Because these bones are wild! They are curious and adventurous and complicated. They aren’t at all what you’d make up; they don’t seem to make any sense; and yet — they work. They work really, really well.”

And it all makes me wonder what would have happened had I learned about science like this when I was a child: science as the greatest art that there has ever been; as something to be revered, and not something to be understood. I will say this: When I moved to Chicago to go to the Art Institute, I did it not in small part because the Art Institute was my favorite museum. The Field Museum has surpassed it. Both are great; but the Field Museum has art that, I’m sorry to say, is better than anything that can come out of the mind of a 20-year-old kid — even if the kid is a long-dead famous artist.