I am writing 100 How-To essays. It is a big project. Here is why I am doing it. This is essay 43 of 100.

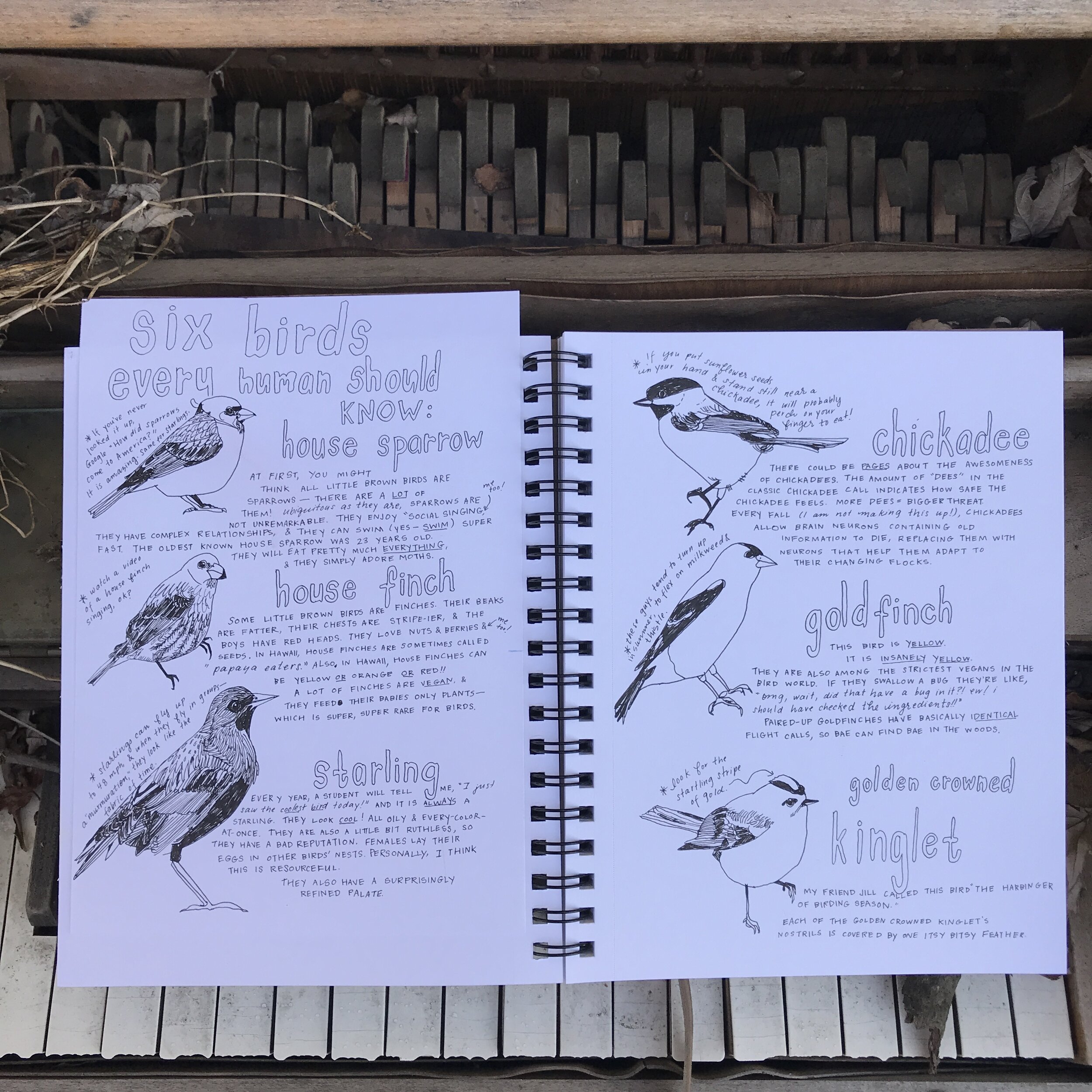

I made a birds-only version of this drawing (I know it’s unreadable up there. There are zoomed in versions throughout this post) that you can download as a PDF and print and give to your kid or your inner kid to color.

For a long time I have told people, with an amount of frustration, that I liked birdwatching before it was cool to like birdwatching. This isn’t actually true, as it has always been kind of cool to like birdwatching. Basically all the cool guys of history have liked it.

Aristotle was super into bird-watching. He was also arrogant (as many of the great thinkers throughout time have been and still are), so he made sweeping false statements about birds. He saw birds disappear in the winter and, even though many early scientists were already onto migration, he told everyone that some birds actually didn’t leave in the winter, but rather hid. He took it a step further and said that some birds transformed into other birds — and still other birds transformed into entirely other things. European redstarts, Aristotle said, reshuffled themselves into European robins in the winter. And the geese that arrived in Greece in the fall, he was sure, bloomed from barnacles that grew on sea driftwood. To this day, we still call that species “barnacle goose.”

The renowned ornithologist John James Audubon was, by all accounts, relatively well-liked. (I know this because I Googled “Did John Audubon have friends?” and the internet said yes he did. He was also married, so two for two.) Pretty much all the famous ornithologists in the early years look like the bad boys of science. (There are a few ladies in there, too: shout out to Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey, who wrote the first modern birding field guide; and Margaret Morse Nice, who studied the heck out of song sparrows and recorded hierarchies in chicken populations decades before a man coined the term “pecking order.”)

The list of cool-guy celebrity birdwatchers is long and diverse. (That’s kind of misleading. They’re almost all straight, upwardly mobile, white guys. But they come from diverse lines of work!) Cool guy president Jimmy Carter is a birder. So is the cool guy of literature Jonathan Franzen. Coolest all around guy Paul McCartney decorated his early homes with bird pictures (specifically, he was into ducks) and wrote the song “Blackbird.” Look at all these cool guys who have been into birds!

And, as I have mentioned before, my mom watches birds. A lot of moms in Oregon watch birds, because if you’re a person who stays home in the Pacific Northwest, you’d be crazy not to. Oregon is lousy with birds. There are more pine trees than anyone knows what to do with. Well, any human. The birds are great at knowing what to do with all those pine trees.

My personal mythology includes a story that is not necessarily true about sitting with my mom at the kitchen window and watching birds while she romantically mused over species names and drew quaint pencil sketches of unique sparrows in a genuine-seeming field notebook. In the fantasy version of this story, I am small enough to curl my legs up underneath me on a kitchen chair, and she is the kind of mom who has made me hot chocolate in the morning, and we are the kind of mother-and-daughter who can be quiet at a window. All three of those latter details are definitely fictional, but I liked the optics.

Here are some things that definitely WERE true about my upbringing as it surrounded birds:

My mom did have a lot of bird feeders, and they did, indeed hang outside our kitchen window. Which was a nice kitchen window — much bigger than any kitchen window I’ve had as an adult — with a view of Mount Hood that I entirely took for granted.

One of the bird feeders was a suet feeder, and it attracted, usually in the afternoon, what seemed like tens of thousands if not trillions of bushtits. Bushtits are, consequently, the cutest living thing. They are ping-pong balls with thistle-thin beaks and anime-black eyes and they bop around and you just want to grab them and cuddle them, which you cannot, because they are fast. As children, my sister and I could, indeed, stare at these birds for a long time. We lost our minds over how freaking adorable they were. We devolved into baby talk while we gushed at them: “Ohhh, wook at da baby widdow oodie woodie woos!” “Oodie woodie woo” became the catchall term for all cute things in the world, and we used it so much that it was my first, seventh, and one hundredth internet password. These days we have to have passwords that are $tuK282019$918321!!Bdjaidio!!!!Jaidfa or we are automatically locked out of our computers. But in the beginning of the internet, your password could be “oodiewoodiewoo,” or, later, “00diew00diew00,” and that was a good password.

My friend Devon had zebra finches and I went over to her house after school three times in elementary school and while I looked at her zebra finches, I thought, “I like birds.” (Devon still teaches me a lot about nature, and I am very grateful that she was TRULY into bird-watching before it was cool.)

When I told my mom about Devon’s zebra finches she told me that she also once had zebra finches, in an apartment in New York, early on in her marriage with my dad. They were named Pooper and Tooter, and according to the story, they were allowed to fly around the apartment. I liked the optics of this, too.

My mom absolutely, at some point in her life, kept a bird journal, and wrote down the names of birds. She also definitely, to this day, has a penciled-all-over Sibley’s Bird Guide, and she bought me one of my own when I graduated high school and went to college. I still have that exact same one. It has had to be taped along the spine a lot of times; it does get a lot of use.

In college, I decided that it would really add to my accumulating manic-pixie-dream-girl cred to be a little too into birds, and to join the Audubon Society. I learned what cedar waxwings were, and when I took boys out to the lake in Walla Walla, I would make up a name for whatever waterfowl was out there and wait until they boy would say, “Oh look! Ducks!” And I would say, “Actually, those are so-and-sos,” and I imagined the boys would be impressed and also curious about me. They’d think, “She is so INTERESTING. No girl has ever taken me to a lake and schooled me about waterfowl. We should kiss.” Mostly, this was for show.

I pause here to say that I am writing this blog post at the beginning of April in the year 2020. That means two things: (1) It is about to be migration season; and (2) we are experiencing a global pandemic, and everyone has to stay inside and not go to bars or concerts or even movies or even really grocery stores if they can help it. Mostly, we all have stacks of books we’ve been meaning to read; and ten streaming services we currently use with enough decent television and movie content to watch for every minute of the rest of human time on earth. Some of us are getting really into baking. Others are just super on Instagram all of a sudden. We all have to have meetings in our private bedrooms while our computers film us. So, ok, there’s plenty to do. But I might argue to you that nothing you can do will give you quite the same kind of pleasure as looking at birds will give you.

And it is so, so easy to look at birds! It is way easier than making sourdough bread, which I have been asked about a lot lately, too. That will be for another blog post on another day.

The honest-to-god truth is that I didn’t really understand looking at birds until I met my husband, Luke. I definitely tried to get him to like me by being quirky about my love of birds, as I had done hundreds of times in the past. But Luke called my bluff, and he got into it, too. And then, in a blink, it was out of control. We were both honest-to-god super into looking at birds. This seriousness started with a well-documented trip to a bird festival in southern Louisiana, where we very nearly died in a lightning storm while camping on the beach, and we saw a swarm of indigo buntings and believed — I am not sure that it was mistakenly — that we’d seen God.

We went on a bird-walking walk two days ago just north on neighborhood streets through Evanston. We saw, and could identify: house finches, cardinals, wood thrushes, juncos, a chipping sparrow, a song sparrow, a million house sparrows, a pair of mourning doves, American robins, murmurations of starlings, and a cooper’s hawk. Also, there was either a crow or a raven, and, humiliatingly, I can’t tell the difference between the two, even while I follow an Instagram account with a regular game called “Crow or No?” where there are weekly quizzes about is this a crow or no. I think that I also saw a wren, but I can’t be sure; it flitted away fast.

On this walk, Luke said, “People are gonna be getting into birdwatching soon; you could write an essay about that and you could sell it and you could get ahead of the curve with this birdwatching writing stuff.” And that was a good idea, but the truth is that no one is going to buy my birdwatching essay. There are enough birdwatching essays. So I’m keeping this one in the family, to encourage you, a person I almost certainly know personally, to look at the birds out your window.

The one thing you probably need to buy is bird seed. If you can get your hands on it, something that’s mostly just sunflower seeds will go the furthest in attracting the colorful songbirds we all covet. They do sell bird seed at Costco, and also Petco is still open in most places. Just make sure you stay six feet away from everyone while you buy your bird seed, and that you wash your hands afterward.

Luke taught me that actual bird feeders are sort of a formality; you can just throw the bird seed all around and the birds will figure it out. You can also easily rig a bird feeder using a plastic bottle. Or there’s the peanut-butter-on-a-pinecone method that is fun for kids to make and all the way biodegradable.

You do NOT need binoculars (although, sure, that’s a fun addition; just don’t assume you’ll figure them out quickly), and you do NOT need a fancy scope. You don’t need anything but stillness, bird seed, and a little bit of outdoor space (a window sill is enough). Put the food out, then sit still. Read a book. Give it a day. And when the birds show up, watch them. House sparrows — which will show up first and are heartbreakingly undervalued — are FASCINATING and strange and have incredible social order. Notice the tiny differences between the birds you see and start to look them up online. The online birding community is weirdly nice; sort of like you’re back in kindergarten again and everyone wants to share and help each other learn stuff.

Also: turn off all the music and podcasts and TV shows and oven fans in your house and listen. See if you can start to match sounds of the birds with pictures of the birds. You should be able to differentiate between robins, sparrows, starlings, pigeons, and cardinals pretty quickly. That feels like a big accomplishment. Then you can start watching videos about, say, how chickadees have a million different calls and they’re all for different purposes.

Aristotle and his thinking ilk have historically liked looking at birds because they’re mysterious and funny and because they make you ask questions: “Why does she have that piece of string?” “Are they pecking each other in anger or are they in love?” “Does this pigeon like me or is she protecting a nest back there?” “What does a nest for one of those little brown jobs look like, anyway?”

I have a weekly scheduled “unusual bird interruption” alarm that goes off on my phone every week in my classes. We watch a bird video for something like two minutes. Afterward, I always say, “If you’re stuck or having a hard time in the world, remember that we share the earth with these creatures! They’re out there, every minute of every day, living their lives, being amazing, and it’s bigger than whatever little thing is going on in our individual lives.” Well, something like that. Lately I’ve just said, “We share the earth with these CREATURES!” And I hope they get it.

For the past several years, I’ve been collecting the emails I get from students — former and current — where they send me pictures of birds they’ve seen out their windows or while on walks. I take it as such a triumph: it means that they are LOOKING while they are living. The time it takes to notice a bird — like, really NOTICE it — is time you are outside yourself. We all need it.

And this, too: It shouldn’t be just straight cis upwardly mobile white guys who look at birds. This year, the Audubon Society finally (FINALLY) put a POC in front of the camera, and the YouTube series is seriously fantastic: watch all twelve of these Jason Ward videos with your free time. And then tell anyone that they have the power to both succeed at and enjoy looking at birds.